Every time I tell a patient they have coronary artery disease, their first response is usually:

“Can you get rid of it?”

My response:

Get rid of it completely?

No.

Potentially get the plaque to reduce in size, become more stable and potentially less likely to cause a heart attack?

Yes.

When evaluating cardiovascular risk, we must always think about three separate categories.

Risk Factors: Smoking, high blood pressure, cholesterol etc.

The Disease: Coronary atherosclerosis (also referred to as plaque)

Events: Heart Attacks & Strokes.

More risk factors, more disease (atherosclerosis), more events.

Fewer risk factors, less disease (atherosclerosis), fewer events.

The evidence is clear that the amount of plaque in your coronary arteries is directly related to your risk of an event, namely a heart attack1.

Therefore, a primary goal is always to minimise the amount of plaque in your coronary arteries to minimise the risk of a major cardiovascular event as much as possible.

The optimal way of having less plaque is by having fewer risk factors in the first place. This is why the emphasis must always be on managing risk factors and not waiting for plaque in the artery to appear before instituting a risk reduction strategy.

But what if the plaque is already there?

And for most people, this will be a reality at some point in their lives, even if they have been mindful of risk factors.

Some risk factors we can measure, but there are those that we cannot. So, therefore, there are always risks. Only some of which we can see and manage.

Visualising Plaque

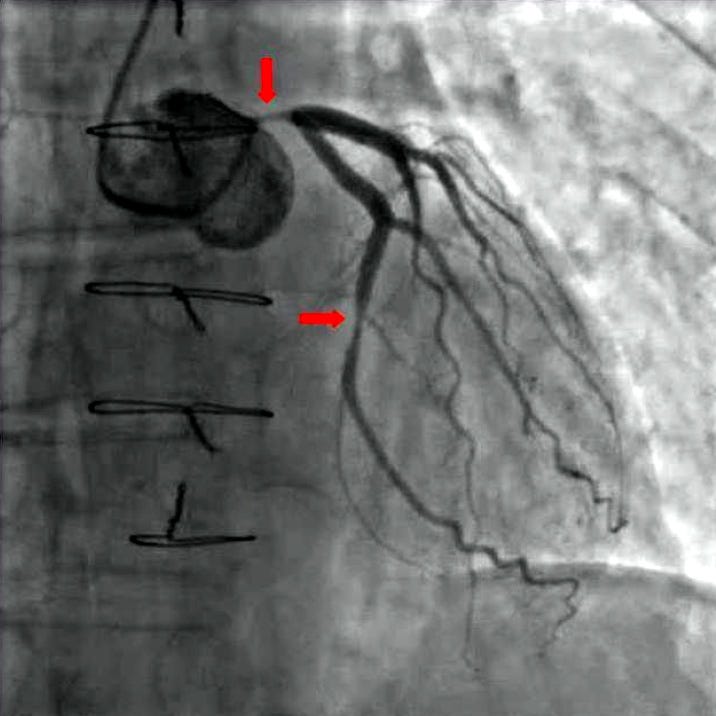

Historically, assessment of coronary artery atherosclerosis was done using invasive angiography, which involved the injection of contrast directly into the arteries and visualising the lumen of the artery under X-ray. While it demonstrates the vessel's diameter loss, it does not visualise the vessel wall where all the plaque has actually built up.

Evaluating the plaque in the arterial wall is best done using a cardiac CT scan or with advanced imaging technologies performed during invasive angiography such as intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography (OCT)

The image above is a CT coronary angiogram demonstrating an artery with a significant amount of atherosclerosis in one of the heart's main arteries. This noninvasive test can also evaluate the type of plaque present, calcified, non-calcified, or a combination of both. This is important, as there are specific types of plaque that are higher risk than others, specifically low attenuation plaque2. With sequential scans, assessments of the amount and type of plaque can be made and how they respond to different interventions or medications.

The two images above illustrate different ways to visualise the composition of the coronary artery wall during an invasive angiogram. The optical coherence tomography (OCT) image on the left and the intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) image on the right can assess the type and amount of plaque in a coronary artery.

Although it is possible to estimate plaque change over time with a basic invasive angiogram, cardiac CT scans, OCT and IVUS are likely the best ways to track changes over time.

Assessing Plaque Regression

Now that we understand how the amount and types of plaque are assessed, we can see how these change with different interventions.

Exercise

The utility of exercise in preventing cardiovascular disease is well established but does it change plaque composition? Assessments of those who are regular exercisers compared to those who do not exercise demonstrate significantly less plaque in the arteries of those who exercise regularly.

But does exercise regress plaque?

The number of studies done in this area is limited, but they show reductions in plaque volume and, more importantly, in the more vulnerable plaques at higher risk of causing a heart attack. Exercise intervention studies have shown reductions of vulnerable plaque by about 3% and reductions in overall plaque volume by almost 11%3.

LDL Cholesterol Lowering

One of the mainstays of managing coronary artery disease is cholesterol-lowering medications. Multiple trials assessing various cholesterol-lowering agents have shown significant reductions in plaque volume.

While it would be tempting to think that one particular agent had an advantage over the other, the evidence suggests what matters is how low the LDL cholesterol is.

The ASTEROID trial investigated high-dose statin therapy in the form of Rosuvastatin 40mg for up to two years. The average LDL cholesterol for these patients at two years was 1.6 mmol/L, and this resulted in an average plaque volume reduction of 6.8%

When combination therapies of more intensive cholesterol-lowering therapies are used, the plaque volumes achieved are even greater. But most importantly, the degree of plaque volume regression was directly related to how low the LDL cholesterol was over time.

The GLAGOV trial used injectable cholesterol-lowering medications called PCSK9 inhibitors to achieve very low LDL cholesterol levels, and the reductions in plaque volume were clear.

The lower the cholesterol, the greater the degree of plaque volume regression4.

When we take all of these studies together, it is estimated that for every 1% reduction in plaque volume, there is a 20% reduction in events such as heart attacks and strokes5.

Conclusion

Almost all of us will develop coronary artery disease at some point in our lives. We know that more plaque equals more risk.

But we also know that plaque in the coronary arteries can be regressed, and doing so can reduce the likelihood of that plaque causing a heart attack.

The key takeaway is that getting your LDL cholesterol to very low levels is essential if you have plaque in your coronary arteries.

LDL cholesterol levels of less than 1.8 and more likely 1.4 mmol/L are most likely to result in coronary artery plaque regression and fewer events.

The questions you need to ask are:

Do I have coronary artery disease?

And

How low is my LDL cholesterol?

Impact of Plaque Burden Versus Stenosis on Ischemic Events in Patients With Coronary Atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Dec, 76 (24) 2803–2813

Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography From Clinical Uses to Emerging Technologies: JACC State-of-the-Art Reviews. JACC Vol. 76 No. 10

Coronary atheroma regression and plaque characteristics assessed by grayscale and radiofrequency intravascular ultrasound after aerobic exercise. Am J Cardiol. 2014 Nov 15;114(10):1504-11.

Effect of Evolocumab on Progression of Coronary Disease in Statin-Treated Patients.The GLAGOV Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016

The effects of lipid-lowering therapy on coronary plaque regression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 11, 7999 (2021).