In 1946, Randy Gardner was part of a Standford University study to assess how long a human could go without sleep and if there were any ill effects.

After 11 days and 25 minutes, he finally fell asleep.

Waking after a 14-hour nap, he claimed that staying awake for so long had no adverse effects. The researchers noting that he had suffered from short-term memory loss, paranoia and hallucinations thought otherwise1.

He suffered from a lifetime of severe insomnia for decades after. Whether it was because of his sleep deprivation experiment is impossible to know.

While it seems very clear that depriving yourself of sleep for such an extended period could not be good for you, the question is, are we all depriving ourselves of much-needed sleep on a daily basis?

While sleep needs vary, short sleep duration is defined as less than 7 hours per night.

On average, 35% of adults sleep less than 7 hours per night2.

Beyond feeling less than well-rested, the question is whether it has any other negative consequences.

“I’ll sleep when I am dead” - Warren Zevon. American Rock Singer

Almost certainly, you have been part of the world’s biggest ongoing sleep experiment, and you don’t even know it unless you are reading this in Japan, India or China, as they don’t use daylight savings time.

Each year, the same articles appear when Daylight Savings time rolls around - “Is it time to get rid of daylight savings?”.

What is much more interesting than these recycled articles is the effects of a sudden one-hour sleep loss or gain on the societies it is imposed on.

Heart attacks go up by 24% when we lose an hour of sleep. But go down by only 21% when we gain an extra hour of sleep3.

Suicides increase when we lose 1 hour of sleep as part of daylight savings4.

Judges give harsher sentences when deprived of that extra hour of sleep5.

Maybe it’s time to set that court date for late October?

Impact On Cardiovascular Health

The relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes, such as heart attack and stroke, is clear. More risks. More heart events.

So anything that worsens these risk factors is a possible contributor to the risk of a heart event.

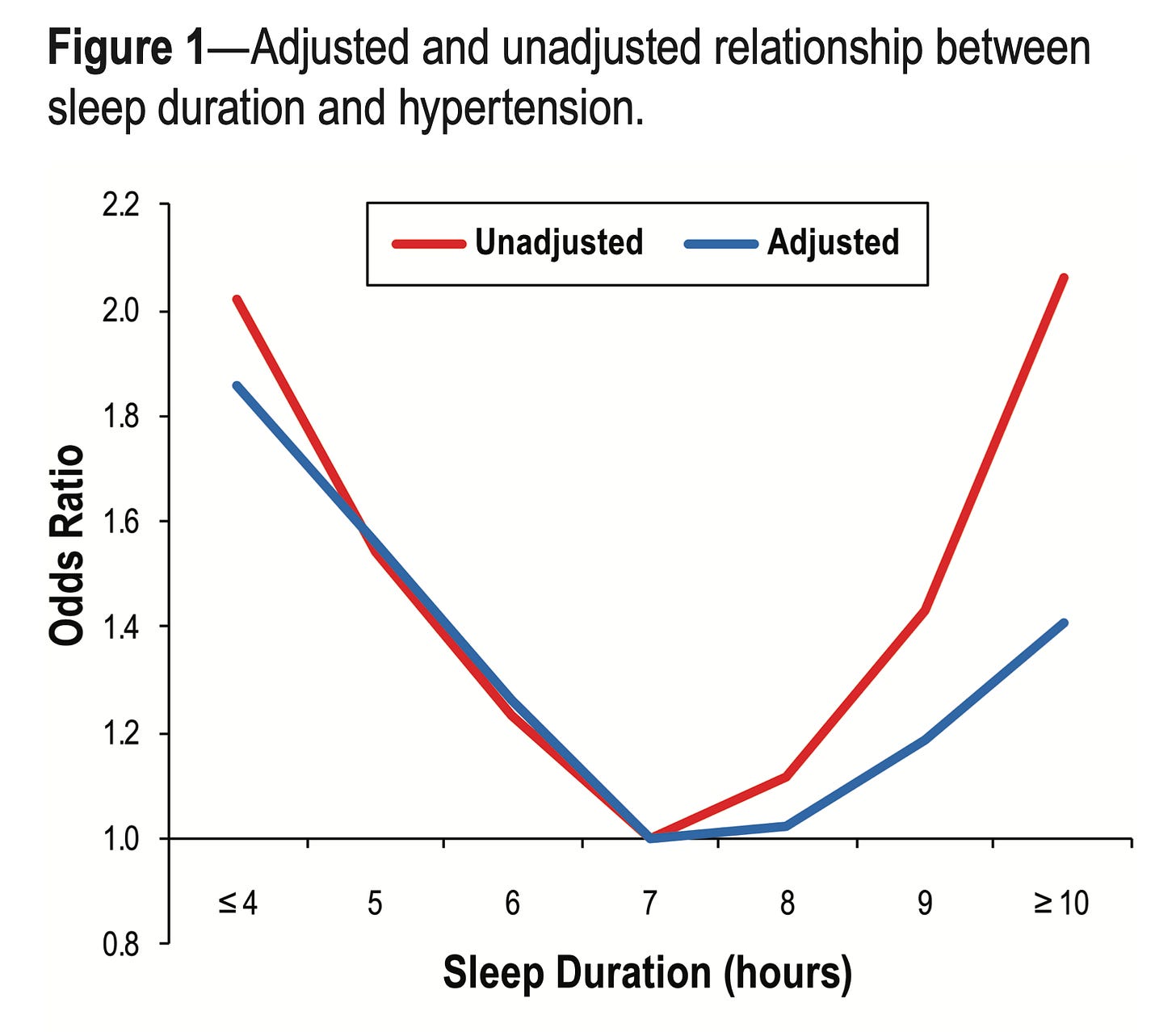

Compared to those who sleep at least 7 hours per night, those sleeping less than 7 hours per night have a significantly increased risk of high blood pressure. The less sleep, the higher the risk. For those sleeping less than 4 hours per night, that risk increased by 86%. Interestingly, those sleeping more than 10 hours per night also had an increased risk of high blood pressure6.

The more plaque in your coronary arteries, the greater the risk of a heart event7. The amount of plaque in your coronary arteries can be assessed with a CT scan of the heart arteries, which gives a result called a 'Calcium Score'. The higher the score, the greater the amount of plaque.

The risk of coronary calcification increases significantly for those sleeping less than 4 to 5 hours per night.

For every hour of sleep lost, the risk of having a higher calcification score went up by 33%8.

With 35% of adults sleeping less than 7 hours per night, it doesn’t exactly bode well for cardiovascular health at a population level.

In addition to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, shortened sleep duration is also associated with an increased risk of dementia. For those in middle age, persistently sleeping less than 7 hours per night was associated with a 30% increased risk of dementia9.

Although most of the evidence cited here is observational data, which is subject to the influence of confounders, the totality of the evidence seems clear.

Beyond the increased risk of certain diseases, poor sleep can significantly impact the quality of your life.

Shortened sleep duration has been linked to dietary interventions being significantly less effective. Even with successfully reducing calories, people on such diets who sleep less than five and a half hours per night are about 55% less likely to lose weight, and the weight they did lose was more likely to be muscle, not fat10. If you are cutting calories, make sure that effort is worth it, and get a good night's sleep.

I firmly believe that sleep is the bedrock of good decision-making in terms of optimising your health. Although biochemical factors drive this relationship, our cognitive well-being is also significantly impacted.

As Nietzsche once remarked:

“When we are tired, we are attacked by ideas we conquered long ago.”

Poor sleep is a foundational pillar of good emotional health. Every one of us can testify to the impact of a poor night’s sleep on one’s mood the following day.

One of the common pushbacks I get when I emphasise the need for more sleep are the examples of Bill Clinton, Margaret Thatcher and Winston Churchill, who achieved incredible success, often sleeping less than 4 hours per night.

My response is simple:

Bill Clinton had a triple bypass at age 58.

Margaret Thatcher developed dementia in her early 70s

Winston Churchill had his first of 8 strokes in his mid-70s.

Not exactly paragons of health. I’m not saying sleep was the only factor here. But get some better examples if you are going to try and convince me!

When I was younger, I thought sleep was a complete waste of time. I was always looking for ways to sleep less. I often asked my friends and colleagues if they could take a pill that would mean they would never again have to sleep but never again feel tired. Would they take it?

I would have.

I possibly still would.

As long as there were no other ill effects.

But in all my reading and research on how to get by with less sleep, I arrived at an obvious conclusion.

I needed more sleep.

I aim to get a minimum of 8 hours of sleep per night. The arrival of a baby has not helped my efforts. And any discussion about the importance of sleep with my transplant surgeon friend with four children, 2 of which are twins, never really goes well.

Having regularly slept 8 hours per night for several years now, I can honestly attest that it has significantly improved the quality of my life.

Now to see if it decreases my risk of a major chronic disease.

I am betting that it will.

But as always, it’s a bet.

But I think a pretty safe one.

Coren, Stanley (1 March 2000). "Sleep Deprivation, Psychosis and Mental Efficiency". Psychiatric Times. 15 (3). Retrieved 2018-03-22.

https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/data_statistics.html

Sandhu A, Seth M, Gurm HS. Daylight savings time and myocardial infarction. Open Heart. 2014 Mar 28;1(1):e000019. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2013-000019. PMID: 25332784; PMCID: PMC4189320.

BERK, M., DODD, S., HALLAM, K., BERK, L., GLEESON, J. and HENRY, M. (2008), Small shifts in diurnal rhythms are associated with an increase in suicide: The effect of daylight saving. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 6: 22-25.

Cho K, Barnes CM, Guanara CL. Sleepy Punishers Are Harsh Punishers. Psychol Sci. 2017 Feb;28(2):242-247. doi: 10.1177/0956797616678437. Epub 2016 Dec 13. PMID: 28182529.

Grandner M, Mullington JM, Hashmi SD, Redeker NS, Watson NF, Morgenthaler TI. Sleep Duration and Hypertension: Analysis of > 700,000 Adults by Age and Sex. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018 Jun 15;14(6):1031-1039. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7176. PMID: 29852916; PMCID: PMC5991947.

JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging May 2015, 8 (5) 579-596;

King CR, Knutson KL, Rathouz PJ, Sidney S, Liu K, Lauderdale DS. Short sleep duration and incident coronary artery calcification. JAMA. 2008 Dec 24;300(24):2859-66. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.867. PMID: 19109114; PMCID: PMC2661105.

Sabia S, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, van Hees VT, Paquet C, Sommerlad A, Kivimäki M, Dugravot A, Singh-Manoux A. Association of sleep duration in middle and old age with incidence of dementia. Nat Commun. 2021 Apr 20;12(1):2289. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22354-2. PMID: 33879784; PMCID: PMC8058039.

Nedeltcheva AV, Kilkus JM, Imperial J, Schoeller DA, Penev PD. Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Oct 5;153(7):435-41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-7-201010050-00006. PMID: 20921542; PMCID: PMC2951287.

For that last 15 years before retirement, I slept 6 -6.5 hours per weekday night, but made up the loss of sleep on the weekends, sleeping as long as I wanted, usually 10-12 hours. (I retired 2 years ago and sleep 9-12 hours unless my alarm is set for an early event). I am not sure how healthy these long hours are. In young adulthood I would set my alarm for 8 hours and always felt refreshed.

Very interesting and useful article. I'd only like to make two points.

a) Those who said Churchill slept four hours are wrong. He slept six every night and napped two more during the day. In fact, he attributed his success in the fact he took naps (he even had a bed installed to take naps while in Parliament).

b) Speaking of Churchill's naps, do they count towards that needed 7-8 hours of sleep?

Naps are quite common in my country Greece and other Mediterranean countries. These countries have generally good life expectancies. Do naps help towards that goal?