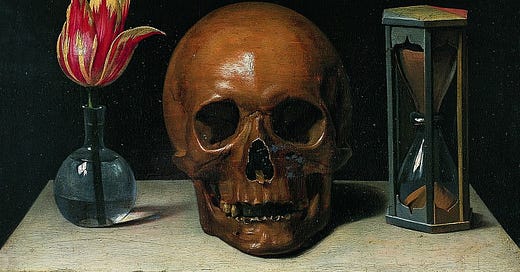

The philosopher William James describes our denial of death, or the recognition of our mortality, as the “Worm at the core”; the driving factor for most, if not all, of our actions in life.

On realising our own mortality, we immediately seek a way to deny it, primarily by trying to achieve immortality, either literal or symbolic.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dr Paddy Barrett to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.